Housing and Driving

HOUSING AND DRIVING: Growth restrictions have displaced workers by Warren Wells

We’ve all heard that California, and Marin in particular, are facing a severe housing crisis. Home values and apartment rents keep rising, leading owners to cash out and renters to be pushed out. We’ve heard from politicians that we need to build more to keep this from happening.

But if there’s one thing Marinites hate more than the high cost of living, it’s traffic. Anyone who has ever had to endure the bumper-to-bumper grind on US 101 or the school pickup line would do anything to keep it from getting worse. How can we allow more housing in Marin when it will just make the traffic worse?What if I told you that more housing would make traffic better? And that the housing crisis and the traffic crisis are actually the same thing?

Traffic on the freeways has gotten worse

First, if you feel like traffic has gotten worse in Marin, you’re right… kind of. On US-101, traffic volumes got steadily higher between 2013 and 2019, but in 2022 (the most recent year we have data for) volumes are lower than they were in 2013. However, the routes into Marin from Solano County (SR-37) and the East Bay (I-580) are as busy as they have ever been (1). While Covid seems to have had an impact on traffic on the 101 corridor, more and more people are trying to get to Marin from the east.

Marin has added very little housing over the last 40 years. To the extent that traffic got worse between 2013 and 2019, and continues to worsen for those coming from the East Bay and Solano County, it certainly isn’t because Marin has built so much housing. The building boom of the 60s and 70s is long over, and housing production has petered out. Today, three quarters of our housing stock was built prior to the Reagan administration. Since 2010, fewer than 3,000 homes have been constructed across Marin, a rate of growth far below many of our neighboring counties.

Cost of housing has risen considerably

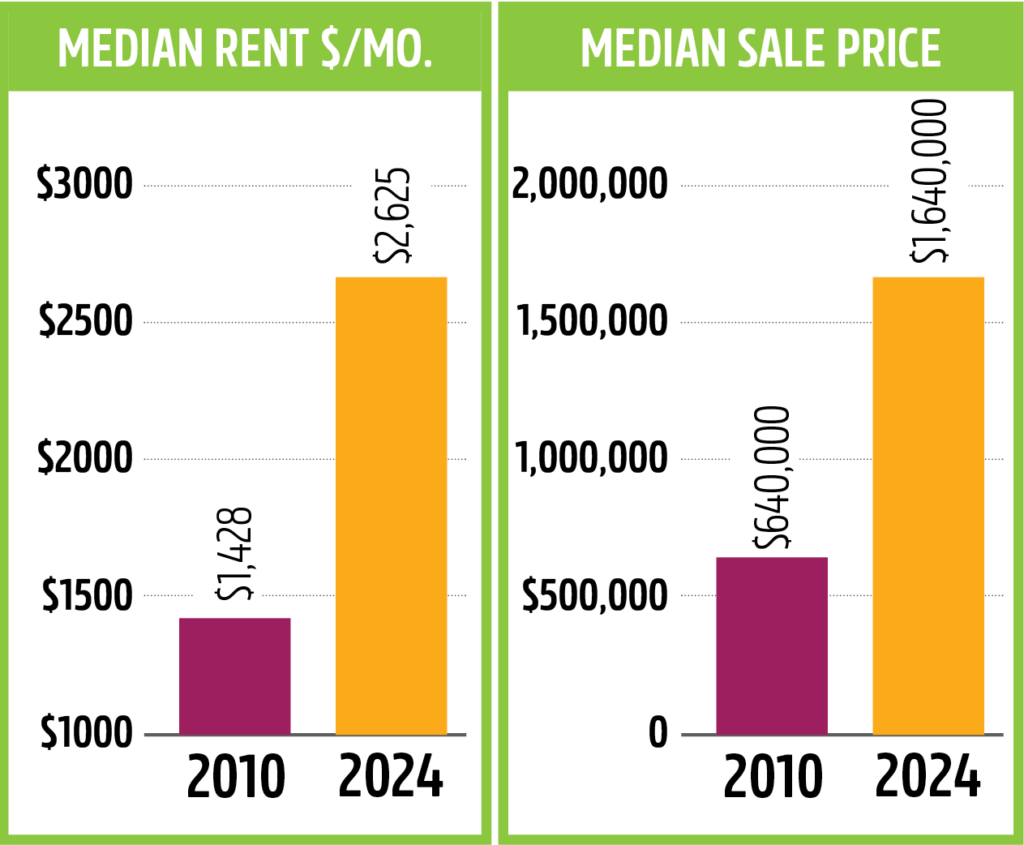

While there is little new housing in Marin, and a relatively small increase in the number of Marin residents, the cost of housing has risen dramatically. Between 2010 and 2022, median rent has increased from $1428 to $2257, an increase of 58%, roughly double the rate of inflation during the same period (2). Home sale prices have also increased substantially. In January 2010, the median home price in Marin was $640,000 (3). Today that figure is over $1.4 million, half a million dollars more than would be expected due to inflation alone (4). Housing is one of the biggest expenses, and it leads to other high costs (childcare, food, etc). When housing prices outpace wages as they have in Marin, people are forced to relocate, or take jobs in Marin without choosing to move there.

People are driving in from Contra Costa and Solano Counties

What has been the effect of the increasing cost of living? People are being pushed out, but some of them still commute to Marin, forcing people into grinding, long-distance drives to work, and clogging SR-37 and the Richmond San Rafael Bridge.

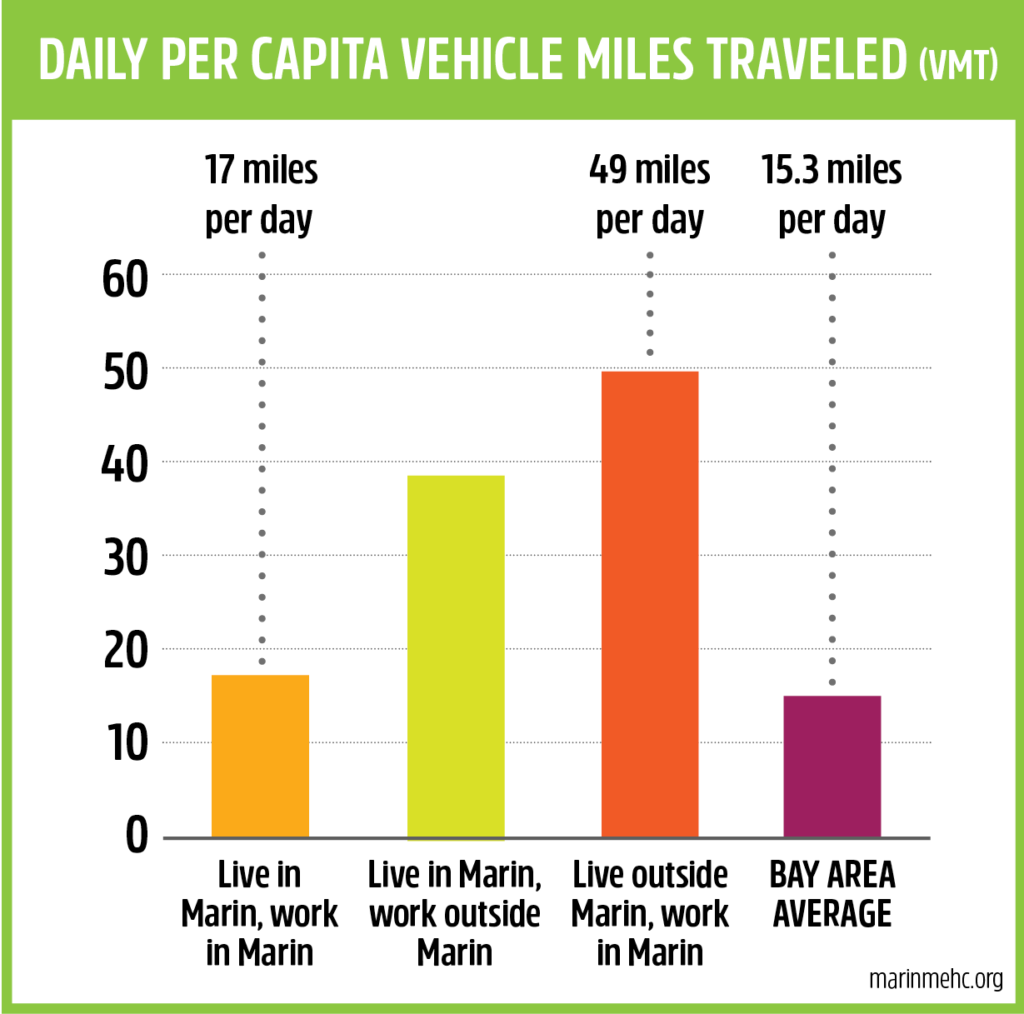

Between 2002 and 2021, the number of people who both live and work in Marin dropped by nearly 10,000, while the number who work here but commute from another county increased by roughly 8,000 (5). This results in substantially more driving, draining hours from people’s days, clogging our roadways and adding carbon pollution to our atmosphere. The average Marin worker living outside the county drives 32 miles farther every single day, roughly an additional hour in the car (7). The number of Marin workers who live over 50 miles away roughly doubled to well over 16,000 (6). If that isn’t a recipe for traffic, we don’t know what is.

What we’re doing isn’t working

To help accommodate all the people who have been priced out of Marin but return here for work, we have committed over $1.2 billion widening highways:

- $800 million: The Marin-Sonoma Narrows project (adding a third lane in each direction of US-101)

- $400 million (and potentially billions more): widening SR-37 between Sears Point and Vallejo

- Unknown tens of millions $: Convert four miles of the Bay Trail to a shoulder and potentially another lane to the Richmond San Rafael Bridge

These projects are bandaids. They seek to accommodate the traffic caused by unaffordable housing in Marin. The trends are clear — more and more of Marin’s workforce is living outside of the county. Building wider roads may alleviate some of the traffic jams (for the time being), but the only thing that reduces clogged roads is housing.

An example from Seattle

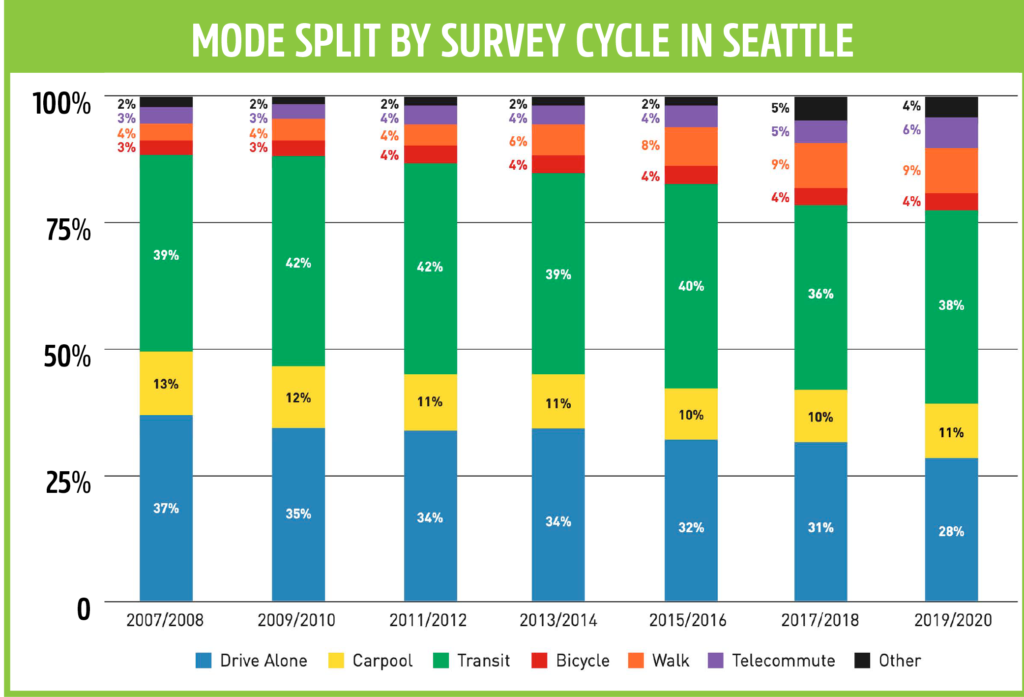

This isn’t just a theory. Seattle shows what happens when a region permits more housing near jobs. Between 2010 and 2018, Seattle grew by more than 130,000 people, a huge population boom by all accounts (roughly a 20% increase). But because the housing was concentrated in the downtowns and on transit corridors, the solo drives to work actually decreased during this period, resulting in less overall traffic.

What to do about it

We’ve seen that keeping a region from growing doesn’t stop traffic from increasing, and that a city can grow and see traffic decrease. The result of the growth restrictions we’ve put in place has simply been to displace workers farther and farther afield, necessitating expensive transportation infrastructure investments to bring them back to the county to do their jobs.

Is this really the best way? Rather than spending billions trying to knock a few minutes off of a 50-mile commute, wouldn’t we be better served by making it possible for people to live closer to where they work? If Marin were welcoming and affordable to workers, thousands of people who work in our schools, restaurants, homes, and communities would also be our neighbors. Their kids would go to school with ours, and we would see them on the weekends at the park. Thousands of people would drive 30 miles less every day, saving gas, eliminating traffic, and reducing stress for everyone. Isn’t that the clean, green, welcoming Marin we all want to enjoy? We certainly think so.

Warren Wells is Policy & Planning Director, Marin County Bicycle Coalition and a MEHC board member

| NOTES AND RESOURCES |

| NOTE: In all references, the most recent traffic data is from 2022. These links refer to (#) notes in text above. 1. Caltrans Traffic Census Program (https://dot.ca.gov/programs/traffic-operations/census) 2. American Community Survey, Table B25058 Median Contract Rent 3. Marin IJ (https://www.marinij.com/2010/02/18/marin-home-sales-up-median-price-drops-to-640000/) 4. Zillow, accessed 4/11/2024 (https://www.zillow.com/home-values/625/marin-county-ca/) 5. US Census Longitudinal Employment Housing Dynamics Survey (https://onthemap.ces.census.gov/) 6. TAM 2017 Strategic Vision Plan (https://www.tam.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/TAM_Strategic_Vision_Plan_FinalReport_112017.pdf) |

MEHC works for the Marin community

Many Marin workers, employers, residents and nonprofits support MEHC’s work to advance environmentally appropriate, culturally sensitive, and socially equitable affordable housing. If that includes you, please consider a tax-deductible donation to MEHC to help us keep working. Your support matters, thank you.