West Marin faces major housing need

The Pt. Reyes Seashore settlement will cause loss of housing and employment for many farmworker families.

– Agnes Cho, consultant and project manager,

Community Land Trust of West Marin (CLAM)

| A West Marin community leader recently shared this comment with me: “In West Marin, finding housing is like winning a golden ticket.” Her offhand statement stuck with me, because finding a place to live shouldn’t take a miracle. But the reality in West Marin is that landing a safe, dignified, and affordable home can feel more like the exception than the rule. Recognizing the deep housing challenges in West Marin, the Committee for Housing Agricultural Workers and Their Families, a diverse coalition of housing, agriculture, philanthropic, and community stakeholders, commissioned the West Marin Housing Action Study. The goal of the study was to better understand the housing needs of lower-income residents and workers in West Marin, with a particular focus on the voices of agricultural workers and their families. |

Severe housing shortage means rents exceed incomes

As part of the Housing Action Study research team, I helped conduct in-depth interviews and surveys with 150 West Marin residents and workers, including many Latinos. We also spoke with local employers, community leaders, and housing and agricultural experts to better understand the housing needs and barriers to building affordable housing in West Marin.

Our study highlighted the severe housing shortage in West Marin. Ninety-three percent of the area’s housing stock consists of single-family homes, with very few multifamily units likely to be affordable rental housing. A large proportion of the housing that does exist is reserved for short-term visitors; more than half the residential properties in West Marin likely are second homes or vacation rentals, with 11% registered as short-term rentals.

The housing shortage deeply impacts West Marin lower-wage workers, many of whom are Latino who have lived there for decades. They are a critical part of West Marin’s workforce and community – the backbone of the dairies and ranches that make up the agricultural sector and the staff for the stores and restaurants that serve the region. Though these workers are central to West Marin’s economy and community, many struggle to make ends meet. The workers interviewed for the Housing Action Study had an average monthly household income of just $3,214, hardly enough in a region where the monthly fair market rent for two bedroom units exceeds $3,300.

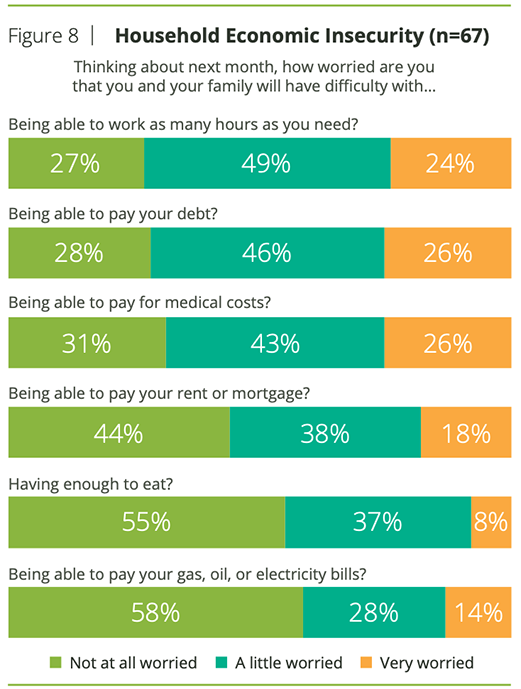

| As a result of the housing shortage and low wages, many Latino workers live in overcrowded and substandard conditions. In interviews and community listening sessions, West Marin workers and residents shared the following experiences: |

- 78% of the households live in housing that lacks basic amenities and poses major risks to their health and safety. Common problems include: mold and mildew that cause asthma and other health conditions; insects and pests in their homes; unpleasant smells; holes in their walls; leaky ceilings; and no heating. Some homes were in such poor condition that, their residents met the federal definition of “homeless” and were included in Marin County’s 2024 Homeless Point in Time Count!

- Renters are afraid to report the poor conditions of their housing fearing eviction and loss of employment, particularly those who are undocumented immigrants or whose housing is tied to their employment–, typically, agricultural workers living on ranches.

- Many lower-wage householders live in overcrowded conditions. Seventy-two percent of households had at least four people living in their home, but most rental units are two-bedrooms or smaller and not designed for larger families. As a result, 40% of households described their housing conditions as “too crowded.””. In 21% of their households, someone slept in a space that was not a bedroom, such as the living room or dining room.

- Eighty-five percent of workers were cost-burdened, spending more than a third of their income on housing. In the past 12 months, 43% of the study respondents had to decide between paying for housing or for other basic needs, such as food or healthcare.

| My home is sinking like the Titanic, it’s falling apart. I would like a house where my kids can sleep how they want and are not uncomfortable. Right now, my oldest daughter sleeps on the sofa, and I sometimes sleep on the floor. |

Severe housing shortage means rents exceed incomes

The study also underscored the ways in which the rental market in West Marin is unique. First, ranches are a critical source of affordable housing for a wide range of lower-wage workers, not just agricultural employees. However, many of these housing units are un-permitted and have inhumane living conditions. Second, the rental market in West Marin is largely informal, segregated, and mediated through social networks. While many Latino renters are often consigned to ranch housing or mobile homes, substandard or not, others have more options for units in residential neighborhoods.

Compounding the existing housing shortage is the imminent risk of displacement. The January 2025 settlement of litigation brought by the Western Watershed Project, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Resource Renewal Institute against the National Park Service will result in the closure of many of the ranches within the Point Reyes National Seashore and will lead to between 90 – 150 Latino farmworkers and family members – who were not consulted nor were r parties to the litigation affecting them – losing their homes as well as their employment. Furthermore, dozens of families live in substandard housing conditions on private ranches, such as Martinelli Ranch, and face the threat of eviction and risks to their health and safety. In total, there are an estimated 50 to 75 families currently living on ranches which are at the brink of eviction, unemployment, and displacement.

When they close a ranch, they take away housing, salary, health insurance. If they keep closing ranches, where do we go?

Conventional approaches are inadequate to this moment

We urgently need far more decent, affordable housing. The Housing Action Study estimates that West Marin needs at least 1,000 new housing units that are affordable to low-income households, and we need to find ways to create this housing far more quickly.

- This is more housing than has been built in unincorporated Marin County over the past 20 years. Between 2018 – 2023, just 200 new housing units were built, and only 29 were affordable to low-income residents.

- Affordable housing projects in Marin can take a decade to approve, finance and build. The families living on the Point Reyes National Seashore ranches and Martinelli Ranch need immediate housing options that are available in months, not years.

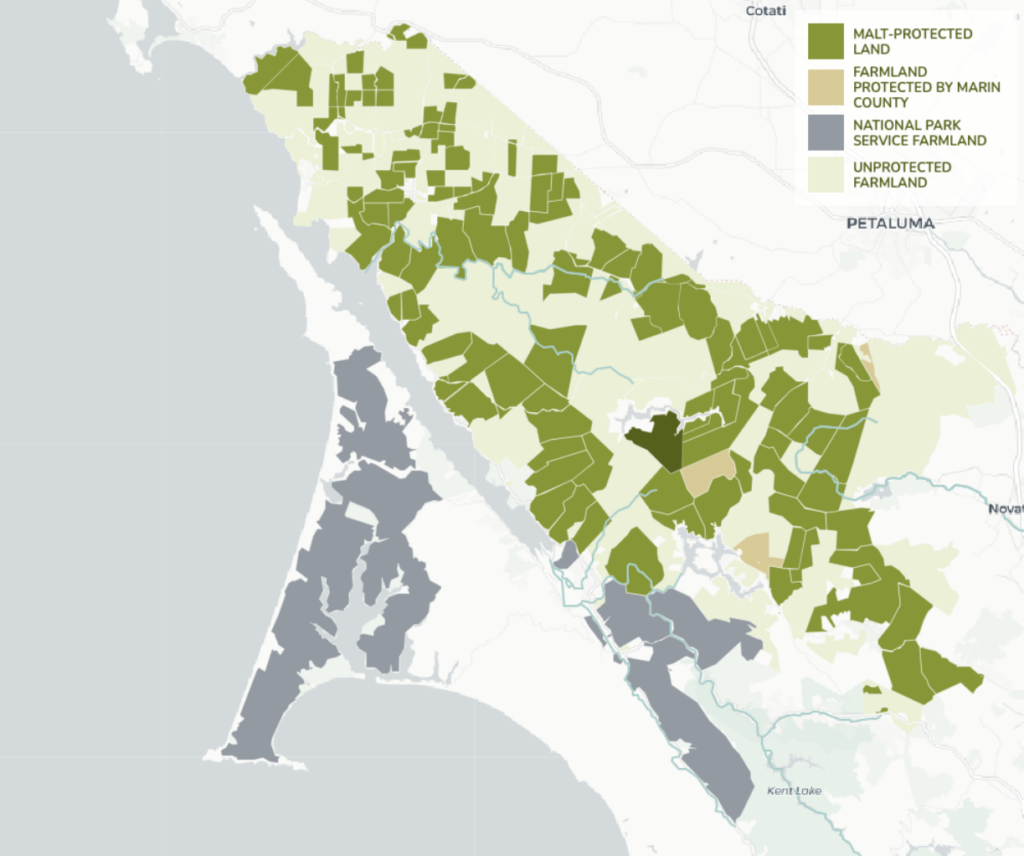

The conventional approach to housing development is insufficient to meet the scale and urgency of West Marin’s housing needs. Our policy decisions have created significant barriers and constraints to development in West Marin. Most of the land is designated for open space, parks, and agriculture, and cannot be used for housing (See map below showing lands protected from development). The California Coastal Commission further limits development and increases building costs and time. Water restrictions and antiquated septic requirements add additional costs and structural barriers to developing new housing. And, unfortunately, the few housing projects that are proposed typically face significant community opposition. (Article continues below)

Great swaths of land in West Marin are dedicated agricultural land, or protected from development. (Source: MALT)

Here’s how you can help

Attend the Board of Supervisors meeting on March 11

The Marin County Board of Supervisors will vote on March 11 to adopt a SHELTER CRISIS DECLARATION. The state bill that established this policy is SB 1395. Our understanding is the declaration suspends local housing, health, and safety standards for the development of emergency housing or “low barrier navigation centers.” The County is also adopting the required alternate building codes on March 11 in order to be compliant with the policy.

If this declaration goes forward, The Community Land Trust Association of West Marin (CLAM) could potentially coordinate with the County to expedite the creation of emergency housing for workers and their families who have been displaced by this Settlement.

Amplifying the voices of West Marin residents

It’s time to change the status quo. First and foremost, we need to amplify the voices and leadership of West Marin’s Latino residents, as they hold the greatest understanding of current conditions and are the most impacted by the housing and displacement crisis. It is disgraceful how the Point Reyes National Seashore settlement process actively excluded the Latino residents who live and work on the ranches. One encouraging sign is the growing organizing and leadership by West Marin’s Latino residents. This includes the work of the Círculo de Esperanza Latina, a committee of Latino leaders who have lived and worked in West Marin for decades. The Círculo identified priorities for the families affected by the Point Reyes National Seashore ranch closures, and West Marin community members, organizations and leaders can help advocate for these solutions.

Marin County leaders have also indicated an openness to considering new and creative solutions. This includes adopting an ordinance to remove local barriers to creating temporary housing as well as considering a policy to give preference to displaced tenants when affordable housing units are available. This moment of crisis is a moment of opportunity to urge the County to take bold action and remove the structural barriers to inclusive development. (See Advocacy Opportunity below) For instance, the County can work towards innovative solutions to environmental and water concerns, rather than using these concerns as justifications against development.

Collaboration will be crucial

Addressing West Marin’s housing shortage and displacement crisis will require unprecedented collaboration. West Marin organizations, government leaders, and community members must come together to align and coordinate collective action. No one organization can accomplish the housing solutions at the scale and speed that it is needed. The Committee for Agricultural Workers and Their Families and the West Marin Housing Collaborative are just a few of the coalitions that are emerging to come together on this issue.

The stakes of West Marin’s housing crisis are high, impacting employers, community cohesion and schools, the tourism and hospitality industry, as well as West Marin’s important agricultural sector. The people who live in the most dire circumstances are the same folks who make our community thrive. We need to update our beliefs that building housing hurts our communities. Instead, we need to acknowledge the reality that the failure to build housing actively harms our community – it creates conditions where people are forced to live in housing that poses health and safety risks and are left with the psychological and emotional trauma of housing instability and displacement.

Marin’s cumulative decisions to restrict housing development have caused this crisis. New decision-making can help fix it. More housing in West Marin will make Marin a stronger, more just, and more inclusive community. Together, as a community, we can create the kind of Marin that serves all its residents, not just a lucky few.